- Home

- Sara Gethin

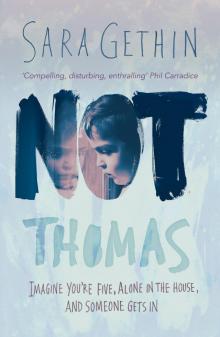

Not Thomas

Not Thomas Read online

Contents

Title Page

Praise

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Waiting for the Christmas Concert

Christmas Holidays

Back to School

Easter Holidays

Not Remembering

Miss Again

Author note

About the author

About Honno

Copyright

NOT THOMAS

by

Sara Gethin

HONNO MODERN FICTION

This novel should be printed on plastic so that the reader’s ample tears don’t blot the paper. Sara Gethin has given us an undeniably memorable character in Tomos, a lovable boy living in the most brutal poverty and abject neglect. It also casts light into the dark shadowlands of child poverty and should act as a reprimand to those who let it continue. Yet Gethin doesn’t forget that the writer’s first job is to hook the reader with a strong story and this one really gets under the skin. A deeply convincing novel that surges with emotion and compassion in equal measure.

Jon Gower, writer and broadcaster

Heart-wrenching, captivating and beautiful. Not Thomas is a poignant portrayal of a hostile world depicted through the eyes of a child. The story stays with you long after you have read the final page. Gethin writes with profound depth and compassion in this exceptionally moving and powerful novel.

Caroline Busher – Irish Times bestselling author

The ability to use sentiment without descending into sentimentality is a rare commodity. But it is something Sara Gethin does effortlessly in Not Thomas. The book is, by turns, compelling, disturbing, enthralling and both physically and emotionally draining. It is, ultimately, an up-lifting tale that is rewarding and an affirmation of the human spirit. Expect to cry, to run the whole gamut of emotions. This is a book that will reward any perceptive reader. It is thoroughly recommended.

Phil Carradice, writer and broadcaster

A thoroughly engaging page-turner. Sara Gethin, with her impressive range of writing skills, takes us to a tragic place, a bleak corner of messed-up lives and hopelessness, but she also shows us the warm spirit of human light that can break through such darkness.

Peter Thabit Jones, Poet and dramatist

For Simon, Rebecca and Jonathan

Acknowledgements

I began writing about Tomos several years ago, when I studied creative writing with the Department of Adult Continuing Education based at Swansea University. I am indebted to my tutors there, particularly Peter Thabit Jones and the late Kate D’Lima, for the enthusiasm they showed for my work and the encouragement they gave me.

I belong to a wonderful writing group, full of talented people who have listened to snippets of my novel as a work in progress. Over the years they have given me insightful feedback and I’ve thoroughly appreciated their advice and friendship.

In 2016, under my real name Wendy White, I submitted a short story based on this novel to the Colm Tóibín International Award, organised by Wexford Literature Festival. I was very encouraged when it was shortlisted, and this gave me the incentive to finish the novel and approach a publisher.

I am hugely thankful to Caroline Oakley, my editor at Honno Press, for taking a chance on the simplistic writing style of this book. It was important to me that Tomos’s experiences should come to the reader first hand. It was his voice I wanted to portray, and I am so grateful that Caroline never once suggested I change the viewpoint. Thank you, also, to Helena, the committee and the whole team at Honno.

Lastly, thank you to my wonderful friends and family – especially my husband, Simon, children, Rebecca and Jonathan, and my mum and dad. Without their love and support Not Thomas would still be just another file on my laptop.

Waiting for the Christmas Concert

The lady’s here. The lady with the big bag. She’s knocking on the front door. She’s knocking and knocking. And knocking and knocking. I’m not opening the door. I’m not letting her in. I’m behind the black chair. I’m very quiet. I’m very very quiet. I’m waiting for her to go away.

I’ve been waiting a long time.

‘Thomas, Thomas.’ She’s saying it through the letter box. ‘Thomas, Thomas.’

I’m not listening to her. I’m not listening at all. She’s been knocking on the door for a long long time. I’m peeping round the black chair. I’m peeping with one of my eyes. She’s not by the front door now. She’s by the long window. I can see her shoes. They’re very dirty. If Dat saw those shoes he’d say, ‘There’s a job for my polishing brush’.

She’s stopped knocking. She’s stopped saying ‘Thomas’. She’s very quiet. The lady can’t see me. I’m behind the big black chair. And I’ve pulled my feet in tight.

‘Thomas?’ she says. ‘Thomas?’ I’m not answering. ‘I know you’re in there. Just come to the window, sweetheart. So I can see you properly.’

I’m staying still. I’m not going to the window. I’m waiting for her to go back to her car. It’s a green car. With a big dent in it. If I hide for a long time she’ll go. She’ll get back in her car and drive away. She’s knocking. And knocking again. She’s saying ‘Thomas.’ And knocking and knocking again. ‘Thomas.’

That is not my name.

‘Thomas.’

I’m trying to think about something nice. I’m trying to remember Cwtchy. I’m trying and trying. I’m remembering his purple fur. And his chewy ears. I want him to be here. I want to hug him. I don’t want to be on my own. Behind the big black chair.

‘Thomas, Thomas. Thomas, Thomas.’

If Cwtchy was here he would whisper ‘Don’t be sad’. And I would whisper ‘I’m not sad anymore, Cwtchy’. And I wouldn’t be lonely. Behind the big black chair. Until the lady goes away.

Knock knock. ‘Thomas, Thomas.’ Knock knock. ‘Thomas, Thomas.’

I’m waiting for the lady to go away. And I’m thinking and thinking about Cwtchy. I’m wishing Dat was here too.

She has stopped knocking. She’s stopped calling me Thomas. I’m listening. I can hear her shoes on the path. The shoes I saw through the window. There are no noises now. My ears are full of quiet. I’m listening through it. I can hear an engine starting. The engine of her car. It’s very rattly. I can hear her car going down the road. Rattle rattle. Rattle rattle. I can hear it turning the corner. Rattle rattle. Rattle rattle. I’m listening hard. I can hear it going away. I’m listening harder. Rattle. And harder. Rattle. I’m listening and listening.

I can hear it gone.

I’m staying behind the chair and I am remembering Dat and Cwtchy. I’m staying here until the yellow light comes on. The yellow light across the road. And then I’m going to go to the cupboard and get some crisps.

* * *

I am up in my high sleeper bed. It’s the bed the lady next door gave me on the day we moved here. She said it was her Jason’s bed. Jason is her grandson. She said he can’t come to stay anymore because he hasn’t got a bed to sleep in now. She said he is rude and he eats too much. Brick borrowed the lady next door’s screwdriver and he turned the bed into bits in the lady’s house. Then he made it into a bed again in my room. There’s a wooden ladder that I climb up. It goes quite high and it has hooks on it. The ladder hooks on the bottom of my bed and it hooks off as well. The bed rattles a lot when I climb up the ladder and it rattles when I climb down. It shakes a lot too. The bed has a sticker on it that says ‘For seven years and up’. I am not seven yet. I am nearly six.

My train table fits under my bed. Dat made the train table for me. Mammy got into Nanno and Dat’s house with her key when Dat was out. Then Mammy and Brick brought my train table here in Brick’s car. A bit of it stuck out of Brick’s boot. That bit of table got wet

in the rain. Mammy got all her clothes too and she brought my trains. But I haven’t got them anymore.

I wish I still had my trains. There’s a blue one and a green one and a red one too. I like the red one best of all. It’s a tippy train. It tips logs. I like tippy trains that tip logs but I haven’t got the red one now. Or the blue one or the green one. Because Mammy sold them to a man called Leper.

I’m looking at one of Dat’s train magazines. Dat gave them to me when I moved to this house. I keep them under my train table. I’m not looking at all the sentences just some words. I’m looking at the pictures too and I am trying to find the words Dat showed me. They are locomotive and turntable and pistons. I’m pulling the clothes all round me. I’m putting Mammy’s jumper on my legs and I’m pulling her tee shirt up to my chin. I am trying to make myself warm.

This is my favourite magazine. It has a picture of a blue engine on the cover. It’s a steam engine and its name is Mallard. I keep it right on top of my pile of magazines. Then I can see it every time I come into my bedroom.

The front door has banged. Mammy is home. She says, ‘Put the kettle on. I’m goin’ for a pee.’ Brick has come back with her. He won’t put the kettle on. She has forgotten that. She’s coming up the stairs.

‘Hello, Mammy.’

She says, ‘You still awake?’ Her words don’t sound right. They are all slidey. Brick is banging in the kitchen. He’s opening and closing the cupboards.

‘The lady with the big bag came,’ I say.

Mammy is saying a lot of rude words.

Brick is shouting, ‘There’s nothin’ to eat.’

Mammy says, ‘There’s crisps in the cupboard by the sink.’ Then she says to me, ‘You didn’ eat all the crisps, did you?’

‘I left the pink packet for you.’

‘Brick don’ like prawn cocktail,’ she says. She’s shouting downstairs again. ‘Blurry social woman’s been roun’ today, so I’ll go to Tesco tomorrow.’

Brick is shouting, ‘Goin’ down the chippy.’

Mammy’s shouting, ‘Bring me somethin’.’ Brick has slammed the front door.

I say, ‘Will you get my big box, please, when you go to Tesco? And my red shiny paper?’

Mammy says, ‘Wha’ you on about?’

‘For me to be a present in the Christmas concert that you’re coming to see. I need it for Thursday. Miss is going to cut holes for our heads and holes for our arms.’ Mammy’s moving the ladder from the bottom of my bed. She’s putting it on the floor. ‘Are you going out again?’

She says, ‘Don’ think so.’

‘Please can you put my ladder back then?’

‘Please can you put my ladder back?’ she says. She’s copying me. But her words have come out all messy. They are slipping over each other. She’s hooking my ladder back on my bed.

‘Thanks, Mammy.’

‘Thanks, Mammy,’ she says in her slippy slidey way. She’s putting off my light. ‘Get in the bath tomorrow, ’fore school.’

‘Okay,’ I say. ‘Will you get them?’

‘Get wha’?’

‘My box and my red shiny paper, please, from Tesco.’

Mammy’s going out of my room. ‘Yeah,’ she says. ‘I will.’

And she’s closing my door tight.

* * *

We are in the big hall in school. We are sitting on the floor and it’s very hard and cold. We have been singing ‘Away in a manger’. Sir has been showing us the words and Miss has been playing the piano. We have been singing for a very long time.

Nearly everyone is quiet now because Sir is talking. ‘What we need is someone with a good voice,’ he says. ‘Someone to sing the first verse on their own. Someone to sing the solo.’

I like the word solo. I’m saying it again and again in my mind. Lots of people want to sing the solo. Sir is pointing to a big girl. She’s waving her hand. ‘Stand up, Alisha, and have a go,’ he says. Alisha is standing up and singing. She has a loud voice. It’s scratchy too. ‘Well done, Alisha,’ Sir says. ‘Who else wants to try?’

He’s pointing to the boy next to me. It’s Eddie. Eddie is standing up. He’s starting to sing. He’s singing ‘Away in a manger, no…’ He’s stopped. ‘I don’t know the rest,’ he says. Some people are laughing.

Sir says, ‘Good try anyway, Eddie.’ Lots of other children are trying. Some of them make the song sound nice. ‘Would anyone else like to try?’ Sir says. No one puts their hand up.

Miss says, ‘What about you, Tomos?’ She’s sitting by the piano. I’m looking at Miss because she said ‘Tomos’ but I know she is talking to a Tomos in another class. He’s a Tomos I don’t know. Miss is smiling at me and I am smiling at her.

‘Who is Tomos?’ Sir says. He’s looking at everyone in the hall. All the children are looking round. We’re looking to see the other Tomos that Miss is talking to. We’re waiting for the other Tomos to put his hand up. He’s taking a long time.

Miss says, ‘Tomos Morris. He’s in my class, Mr Griffiths.’ Miss is still smiling at me and I’m still smiling back. She’s waving her hand. I’m looking and looking at her. She’s waving it again. ‘Get up, Tomos,’ she says.

‘Me, Miss?’

‘Yes, Tomos,’ Miss says. She’s still smiling. ‘You.’

I’m getting up. I’m getting up slowly.

‘Oh bless,’ Mrs Caulfield says. She’s Carrie-Anne’s helper. She helps Carrie-Anne push her wheely chair. ‘Leave the poor kid alone.’

I’m standing up now. Everyone in the hall is looking at me. The children are looking at me and the teachers are looking at me too. Miss is starting to play the piano. I’m taking a big breath and I’m filling myself up. I’m making myself big with a big breath. I’m singing ‘Away in a manger, no crib for a bed, the little Lord…’ all the way to the end.

I’ve stopped singing and Miss has stopped playing the piano. She’s pushing a bit of her brown hair behind her ear. ‘Well done, Tomos,’ she says in a quiet voice. She’s still smiling at me. Her smile is very big. I’m sitting down again.

‘Well, well,’ Sir says. He’s looking at me through his big glasses. ‘Well, well.’ He’s shaking his head and smiling. He’s smiling and smiling at me. ‘Who’d have thought it?’

* * *

I’m running to Kaylee and her mammy. They’re standing outside school. ‘So you’re singing the solo?’ Kaylee’s mammy says. ‘In the Christmas concert?’

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘I’m singing the solo.’ I’ve been saying the word solo all day in my mind. Solosolosolosolo.

Kaylee’s mammy is rubbing my shoulder. ‘You take after your mother, you do. She’s got a great voice too.’

‘Has she?’ I say. We’re walking now. Kaylee and her mammy are walking to their house and I’m walking with them.

‘Oh yeah,’ Kaylee’s mammy says. ‘Haven’t you heard your mother singing? She used to sing a lot in school. She got to sing all the solos too.’

I’m trying to remember if I’ve heard Mammy singing. I’ve heard Nanno singing. She used to sing to me every night when I went to bed. When I lived in her and Dat’s house. She used to sing lots of songs but I don’t remember Mammy singing at all. ‘I haven’t heard her,’ I say.

‘Oh well,’ Kaylee’s mammy says.

We’re still walking. I’ve remembered a song Nanno used to sing to me. It’s her favourite song and it’s my favourite too. I’m singing ‘Calon lân yn llawn daioni…’ I’m singing it all the way to the end.

‘That’s lovely, that song is,’ Kaylee’s mammy says. ‘I don’ know what some of those Welsh words mean though.’

‘Nanno showed me how to sing it another way.’ I’m singing ‘A pure heart that’s full of goodness, is fairer than the…’

I’ve stopped singing because we’ve come to our gate and I can see Mammy in the front room. I can see her pretty yellow hair. ‘Mammy’s home. My mammy’s home!’ I’m shouting it and I’m running up the path.

‘See you tomorrow,

’ Kaylee says.

‘See you tomorrow,’ I say.

Kaylee and her mammy are going down the road and I’m running up the path fast to Mammy. I’m going into the kitchen. ‘Hello, Mammy,’ I say. ‘Hello, hello, hello.’ I’m hugging her legs.

‘Eat this.’ She’s giving me a plate. It has three fish fingers and some chips on it.

‘Thank you, Mammy.’

I’m sitting on the settee with Mammy and I’m eating my fish fingers and chips and they’re hot and yummy and we’re watching people trying to win money on the telly and Mammy’s texting on her phone too.

‘You ’ad fish fingers for tea yesterday.’ She’s saying it to me but she’s still texting.

I’m trying to remember yesterday. ‘I had crisps for tea yesterday,’ I say. ‘After the lady with the big bag went away.’

‘You ’ad fish fingers, okay?’

‘I had crisps,’ I say. ‘A blue packet and a green packet. I left the pink one for you.’ I’ve got the last bit of chip in my mouth and I’m trying not to chew it because I want to make it last a long long time.

‘Just say you ’ad fish fingers.’ She’s saying it slowly.

‘I had fish fingers.’ I’m saying it slowly too.

‘Yeah,’ Mammy says. ‘Tha’s right.’ Her phone is buzzing. She’s looking at it. ‘Remember to say tha’ when the social woman comes.’

‘The lady with the big bag?’ I’m chewing my last bit of chip. I’m chewing it fast now and I’m swallowing it. ‘Is she coming again today?’

Mammy’s texting. ‘Yeah,’ she says.

‘Are we waiting for her? Is she coming now?’

‘Wha’ do you blurry think? Did you ’ave a bath this mornin’?’ I’m nodding. Mammy’s putting her face next to my jumper. ‘Don’ smell like it.’

‘I washed my hair too,’ I say. I’m remembering this morning. I’m remembering the bath. The water was very cold and I was shaky shaky shaky. I tried to make a bubbly hat with shampoo like Nanno used to make. It was very hard and the bubbles went down my face. They went in my eyes and it was hard to make the prickly go away. But I tried to wash my legs like Nanno showed me and my arms and my bottom. And my front and my neck and my face but my eyes were still prickly. They were still prickly when I was watching for Kaylee and her mammy. And they were still prickly when we were walking to school. Kaylee’s mammy said, ‘Your hair’s all wet.’ And I said, ‘I’ve had a bath.’ And Kaylee’s mammy said, ‘Your eyes look sore.’ And I said, ‘I got bubbles in them.’ And they were still prickly when we got to school. And Kaylee’s mammy told me to go to the toilets and put water on my eyes. After I did that they didn’t hurt so bad.

Not Thomas

Not Thomas